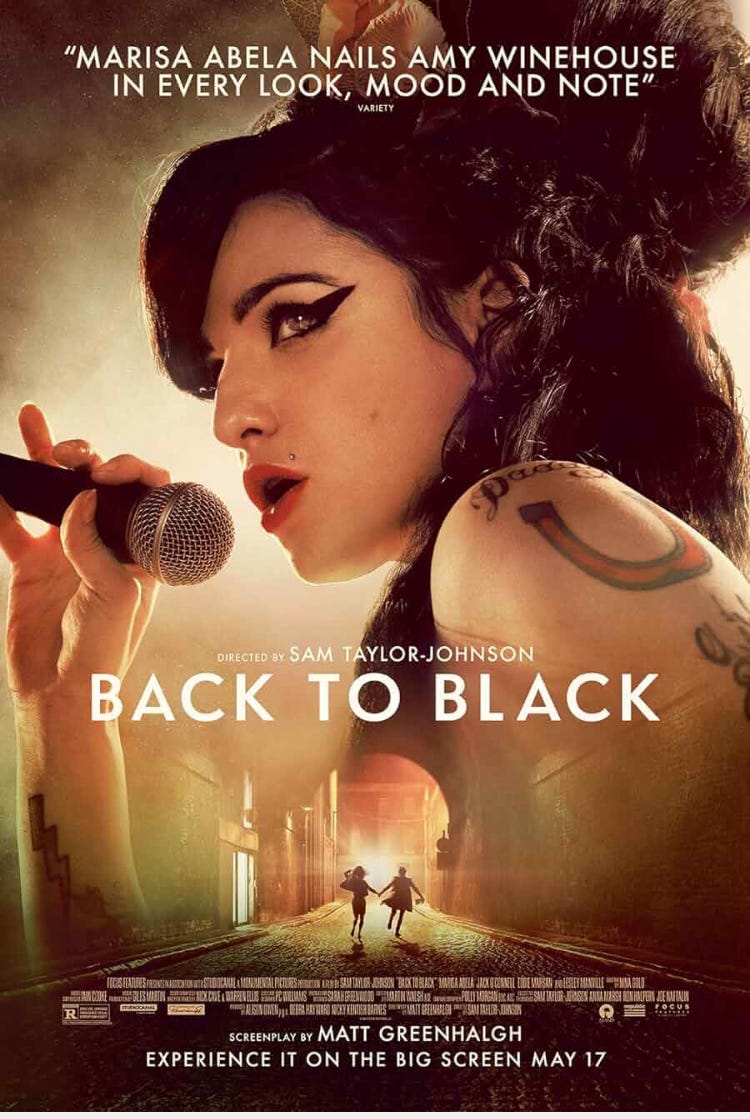

Neither as great as it could have been nor as awful as it might have been, Back to Black has at least one viable reason for existing: Marisa Abela’s soulful star turn as Amy Winehouse is truly captivating.

I will happily admit the British actress, known for her role in the BBC series Industry, comes closer to embodying the late singer songwriter’s physical, vocal and spiritual presence than I thought possible beforehand.

The fact that she also comes across as (more than a) little sweeter than Winehouse also works in the movie’s favor, as it makes it easier to sympathize with the hardships she has to gothrough: her addictions, her life with Blake Fielder-Civil, the constant media attention and the death of her grandmother, who has was also her role model and style icon.

Director Sam Taylor-Johnson (Nowhere Boy) deftly makes sure we see the world through Amy’s eyes at all times. Blake is played by Jack O’Connell, who makes him look, not as a total idiot, but as she must have seen him: handsome, intelligent and even charismatic.

There is a wonderful sequence early on in legendary London pub The Good Mixer, where they first meet. He first pretends he doesn’t know who she is and later schools her on Leader of the Pack by sixties girl group The Shangri-Las, a legendary song (written by producer George ‘Shadow’ Morton together with famous songwriter duo Jeff Barry and Ellie Greenwich) she’d never heard, even though her own vast musical knowledge went right back to the great jazz singers of an even earlier age.

It is love at first sight and even though Amy soon realizes Blake does coke (‘Class A-drugs are for mugs’ she used to say) it’s not enough to come to her senses, and see him for what he is: bad, bad news.

Back to Black is told as a tragic love story, with writer Matt Greenhalgh (Control, Nowhere Boy) drawing inspiration from Winehouse’s lyrics for her second album, which was mainly about her turbulent relationship with Blake. (And also about the fact she didn’t want to go to Rehab, as her addictions were already hurting her a lot - the decision not to go was apparently supported by her father).

Artistically sound as this approach may be, there are limitations to this approach, as the movie doesn’t offer any real insights into her personality that we don’t already know about from the brilliant documentary Amy (2015) by Asif Kapadia, which was created entirely from archival footage and some testimonials.

‘I’m an addict,’ she admits to her father Mitch (Eddie Marsan), towards the end of the movie, and that’s as deep as it gets. Well, that and the idea that ‘Love is a losing game,’ to quote one of her other famous song titles.

Mitch, who was often seen as the driving force behind Amy’s career and was said to be motivated mostly by money, is basically portrayed as a saint here, which I guess isn’t strange as the movie was made with the approval of the Winehouse family.

Taylor-Johnson has made it clear in interviews she didn’t want to play the blame game, but in a movie told from Amy’s perspective, her relationship with her father, who was so instrumental to her career, feels quite undernourished. He is there, from time to time, but more as a presence than as a rounded character with an actual arc.

The filmmakers have trouble deciding what’s important to the story. At one point an executive tells Amy he is going to introduce her to a young producer called Mark Ronson. But we never meet him, not even in the studio when recording Back to Black. It’s as if mentioning him is enough and everyone in the audience knows who he is and how important he was in making that legendary album.

There is quite a lot of music in the movie, both on stage and on the soundtrack, but there is not a lot about the creative process. Early on Amy talks to her grandmother about love, then goes to her room, plays her guitar and writes a song - or perhaps finishes a song she has been writing. It’s adequate, it just doesn’t tell us very much.

The creative forces also shy away from questioning the intrusive role of the media too much, in particular the paparazzi who must have made her life a living hell: sometimes Amy played them for a bit, quite often they just bullied her beyond belief. But the filmmakers never really analyze the effect it must have had on her. Or, and I’m just spitballing here, how she became an alcoholic at such a young age. The answers don’t always have to be spectacular, but the filmmakers could have tried a little harder.

Keep reading with a paid subscription!

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to A Celebration of Cinema to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.